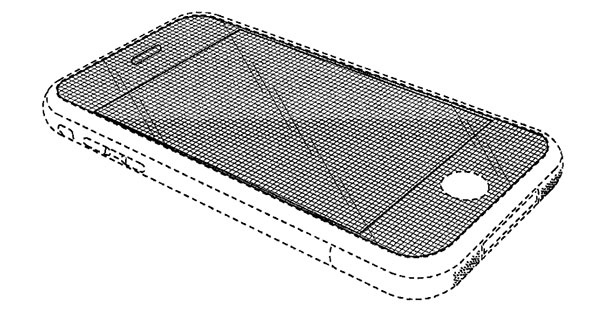

Interesting things are still happening from time to time in connection with the generally much less interesting patent dispute between Apple and Samsung. Three months after the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit vacated $380 million in damages, thus necessitating a third trial in the first California case between these parties, but upheld approximately $547 million in mostly design patent-related damages, it looks like one of the patents underlying that damages claim should never have been granted in the first place.

On August 5, 2015, the Central Reexamination Division of the United States Patent and Trademark Office issued a non-final action in the reexamination (requested anonymously, by Samsung in all likelihood, in mid-2013) of U.S. Design Patent No. 618,677, an iPhone-related design patent. While technically non-final, the odds are long against Apple getting this patent, shortly referred to as "D'677" in the Samsung litigation, upheld. I'm so very skeptical because the USPTO has taken a long time since the filing of the reexamination requests to issue this Office action and, which is far more meaningful, it has determined that this design patent's single claim "stands twice rejected under 35 U.S.C. 103(a) [obviousness], rejected under 35 U.S.C. 103(a)/102(e) [obviousness in connection with a published patent application], and rejected under 35 U.S.C. 102(e)."

The problem the D'677 patent faces here is that the USPTO has determined (for now) that this patent "is not entitled to benefit of the filing date" of two previous Apple design patent applications because the design at issue was not disclosed in those earlier applications. As a result, certain prior art is eligible now, and against the background of that additional prior art, the USPTO believes the patent shouldn't have been granted.

The first rejection for obviousness is based on the combination of U.S. Design Patent No. D546,313 (obtained by LG, another Korean device maker) with either this Sharp patent application or some Japanese design patent application (JPD1235888).

The second rejection cites another Japanese design patent, JPD1204221, in combination with various other prior art, including among others a Samsung design patent (U.S. Design Patent No. D546,313).

The third rejection for obviousness combines one of Apple's own design patents, U.S. Design Patent No. D602,014 with other prior art.

Yet another Apple design patent, U.S. Design Patent No. D618,204, forms the basis of the fourth rejection.

The USPTO's holdings and findings call into question the legitimacy of Apple's intent to collect roughly half a billion dollars in design patent damages from Samsung. Apple's design patent damages claims have been considered outsized by 27 U.S. law professors as well as several of Apple's most significant Silicon Valley neighbors including Google, Facebook, and HP.

Just last Friday, the Patently-O blog published a guest post by Gary L. Griswold, former President and Chief Intellectual Property Counsel for 3M Innovative Properties Company, who disagrees with the Federal Circuit's decision to deny Samsung's request for a rehearing. To me, that denial was no surprise after a unanimous panel decision, and the only interesting question here is whether Samsung will file a petition for writ of certiorari with the Supreme Court. The Patently-O blog believes "Samsung will almost certainly" do so, and while I can't offer a prediction here, I strongly hope that it will because this issue is a serious threat to innovators. Mr. Griswold fears an "explosion" of design patent lawsuits and sees "troubling signs that increased assertion activity has already begun." If that is so, the Supreme Court may actually be interested in looking into this issue now and may overrule the Federal Circuit.

Mr. Griswold argues that courts should not allow a disgorgement of total infringer's profits over a design patent unless the patented design at issue really drives demand for the product. That is an interesting approach but there are other ways to solve the problem, such as the one proposed by industry body CCIA last year.

The bottom line is that Apple's design patent enforcement faces two kinds of legitimacy problems: widespread opposition against the idea that unapportioned disgorgement of profits is an appropriate remedy for design patent infringement by highly complex technology product (imagine what would happen if someone tried to collect all of Facebook's profits over a single icon) and now the USPTO's assessment that one of those iPhone design patents is actually invalid.